Boosters

By Malcolm Peirson

The LNER was probably the only British railway company to experiment with the fitting of boosters.

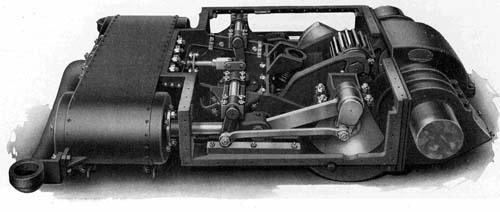

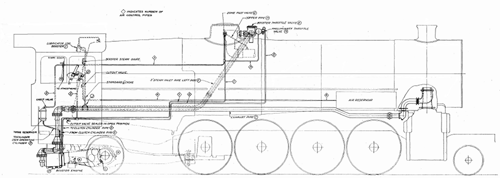

A booster is actually a secondary steam engine provided on a locomotive's trailing axle or tender to assist with train starting. The booster is intended to address two fundamental flaws of the standard steam locomotive. Firstly, most steam locomotives do not provide power to all wheels. The amount of force that can be applied to the rail depends on the weight on driven wheels and the factor of adhesion of the wheels against the track. Unpowered wheels effectively 'waste' weight which could be used for traction. Unpowered wheels are generally needed to provide stability at speed, but at low speed this is not necessary. Secondly, the "gearing" of a steam locomotive is constant, since the pistons are linked directly to the wheels via rods and cranks. Since this is fixed, a compromise must be struck between ability to haul at low speed and the ability to run fast without inducing excessive piston speeds (which would cause failure) or the exhaustion of steam. This compromise means that the steam locomotive at low speeds was not able to use all the power the boiler was capable of producing? it simply couldn't use steam that quickly, and there was a big gap between the amount of steam the boiler could produce and the amount that could be used. The booster enabled that wasted potential to be put to use. Therefore, to assist with starting a heavy train, some locomotives were provided with boosters to utilize this extra steam (Fig. 20 shows a drawing of a typical booster). Typically the booster engine was a small two cylinder steam engine back-gear-connected to the trailing pony truck axle on the locomotive or, if none, the lead truck on the tender. A rocking idler gear permitted it to be put into operation by the driver. It would drive one axle only and could be non-reversible with one idler gear, or reversible with two idler gears. Used to start a heavy train or maintain low speed under demanding conditions, the booster could normally be cut in while moving at speeds under 15 mph. Rated at about 300 hp. (224 kW) at speeds of from 10 to 30 miles per hour it would automatically cut out at 30 mph (Fig. 21 is a diagram of a typical booster layout).

Locomotives Fitted With Boosters

Even before the formation of the LNER, H. N. Gresley, the Locomotive Superintendent of the Great Northern Railway, was considering the fitting of a booster to an Ivatt C1 Atlantic and No. 1419 (later No. 4419) appeared so fitted in 1923. The booster was a small two cylinder engine incorporated in the trailing pony truck which, in theory, improved the tractive effort by about 50 percent. The booster could be engaged by means of compressed air supplied by a Westinghouse pump (eventually replaced by a steam system) and had cylinders that were 10 in. by 12 in. and were connected to the axle with gears of total ratio 36:14. After extensive trials around the Bishop Auckland area and many refinements, including a new gear ratio of 36:24, Gresley was still not too happy about the riding qualities of No. 4419 and wrote a letter that was to lead the way to another class of locomotive being fitted with boosters. Because of these riding problems, and other niggling mechanical difficulties, the booster was subsequently dismantled on No. 4419 in 1935.

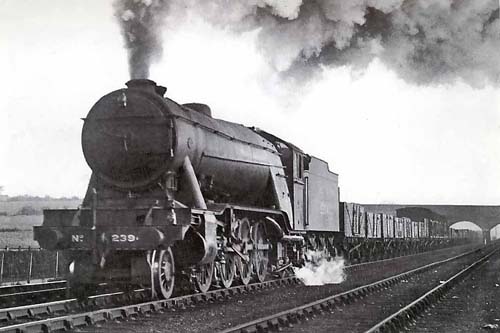

However, results were encouraging enough for Gresley to have boosters fitted to his two new large freight locomotives: the 2-8-2 Class P1. The first of this pair appeared in June, 1925 (No. 2393) with the second (No. 2394) appearing in November of the same year (Fig. 22 shows No. 2394 with the booster operating). Despite being well liked, early trials showed that the boosters were only effective with loads of at least 1,600 tons, and because typical loads were much less than this, coupled with the fact that the steam pipes leading to the boosters leaked, the boosters were removed in 1937 (No. 2394) and 1938 (No. 2393).

In November 1926 Gresley wrote to A. C. Stamer, the Assistant Mechanical Engineer stationed at Darlington Works, as follows:

During 1927 drawings were prepared for this modification as envisaged by Gresley, but although a new tender was to be provided the engine was to be very little altered. In 1928 further drawings were prepared showing the engines as actually rebuilt in 1931, with a new tender and extensive alterations to the locomotive. In the meantime Gresley had approached Messrs. Stones regarding the supply of a booster and he was offered suitable equipment at 875 pounds per set - for a minimum order of five sets. Instructions were therefore given for Darlington Drawing Office to investigate the possibility of fitting a former GCR 0-8-4T Class S1 with a booster. These particular locomotives had been built for the Wath-on-Dearn marshalling yard in South Yorkshire, but difficulties sometimes occurred with wet slippery rails, and on occasion two had to be used together to push large consists over the hump.

This scheme proved feasible and in November, 1928 Gresley approached the Chief General Manager of the LNER for authority to build two similar 0-8-4Ts, thus accounting for the five sets of booster gear on:

- 2x Class C7 4-4-2 rebuilt

- 1x Class S1/2 0-8-4T rebuilt

- 2x Class S1/3 0-8-4T built new

The main reason for the fitting of boosters to the two North Eastern Atlantics appears to have been to do away with double heading of passenger trains between Edinburgh and Newcastle, necessitated by the 4.5 miles of 1 in 96 up Cocksburnspath. For this reason the booster was designed so that it could be engaged at speeds of up to 30 m.p.h.

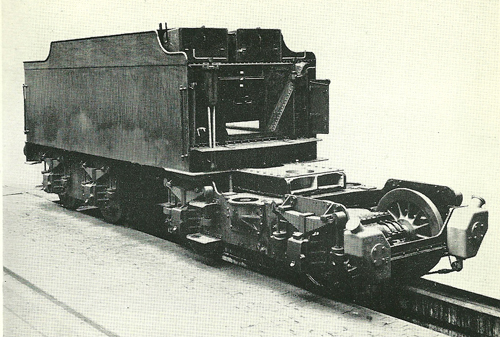

No. 727 and No. 2171 were chosen as the guinea pigs and both were completed in 1931. In 1932 there was some discussion as to the future classification of the two engines which were still referred to as "Class C7 with booster". The Locomotive Running Superintendent pointed out that the engines had been described to him as having a 4-4-4-4 wheel arrangement, which under the LNER system of classification would have required a letter of the alphabet to indicate this. For simplicity it was decided to refer to them as having the 4-4-2 wheel arrangement so that the letter C could be used. In February, 1932, therefore, they were reclassified C9 (Fig.23 shows No. 727 ex works).

With regular footplate crews the two engines performed satisfactorily on the main line between York and Edinburgh.

However, when they became 'common user' engines the booster equipment soon fell into dis-use and it was removed

from No. 2171 in December, 1936, and from No. 727 in February, 1937

(Fig. 24 shows the booster arrangement on the bogie). Because of their non-standard design these two engines were

withdrawn in April, 1942 (No. 2171) and January, 1943 (No. 727). A point of interest here is that after standing

idle for five years the two tenders (suitably modified in 1945) were attached to

Class B1 4-6-0 Nos. 1038 Blacktail &

1039 Steinbock.

As for the three S1 engines, after being superheated to provide extra power for the boosters, all three engines had their boosters removed in 1943. They survived into nationalization and were eventually scrapped between 1956 and 1957.

The booster saw most use in North America and railway systems elsewhere often considered them costly to maintain with their flexible steam and exhaust pipes, idler gear etc. The complexity of the booster when set against the gains made them, in many cases, unjustified. Even in the North American region, booster engines were applied to only a fraction of all locomotives built.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Euan Cameron and Allan Rogers of the North British Railway Study Group for kind permission to use Euan's drawing of No. 224 and background information.

Also, kind thanks to George Moffat for permission to use the image of No. 727, and to '65447' of the Great Eastern Society for providing background information on the G16, and images that enabled me to produce the line drawing.

And finally, thank you to the playwright John Moorhouse for proofreading, editing, advice, and constant encouragement and support.

Bibliography

"The North Eastern Atlantics", by K. Hoole; Publ. Roundhouse Books.

"Locos of the North Eastern Railway", by O. S. Nock; Publ. Ian Allan Ltd.

"The North Eastern Railway. Its Rise and Development" by W. W. Tomlinson; Publ. Longmans, Green and Company.