The Gresley C9 4-4-2 Atlantics

Compared to many other British main lines, the East Coast main line generally lacked severe gradients, but trains heading south from Edinburgh had to climb Cockburnspath Bank, a 4.5 mile winding gradient of 1 in 96. Double heading of heavy passenger trains was essential before the A1 Pacifics appeared in large numbers, and very common in the early days of the LNER. Gresley considered double heading wasteful, and created the C9 Class by rebuilding two Raven C7s with boosters as an experiment to solve the problem.

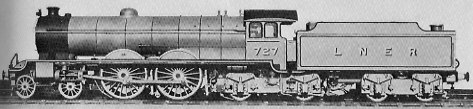

Before Grouping (1923), Gresley had studied USA booster performance and had rebuilt one Ivatt C1 Atlantic with a booster on the rear pony truck. During the mid-1920s, the rebuilt C1 performed a series of trials on the Cockburnspath Bank. Fitting the booster to the rear pony truck of the C1 suffered from the large weight of the booster (20 tons), and the lack of space for adequate springing for a smooth ride. To overcome these problems, a scheme was devised where the pony truck was replaced with a two axle bogie that was also shared with the tender. The scheme was developed into a plan to rebuild two C7s with boosters and larger boilers. Nos. 727 and 2171 entered Darlington for repairs in early 1931, and selected for these rebuilds. Both left Darlington for trials at the end of 1931. There was some early confusion over their designation. During early trials they were referred to as 'C7 with booster', but the Locomotive Running Superintendent has been quoted as saying that they were described to him as '4-4-4-4's, ie. an articulated tank locomotive! For simplicity in incorporating the engines in the existing LNER classification scheme, the booster was considered split between the engine and the tender to give a 4-4-2 with 6-wheeled tender. From February 1932, they were officially classed as C9.

Booster trials with C1 No. 4419 showed that the booster was of little use over 25mph, although operation at 30mph was required for hauling expresses. Hence, Darlington recommended changing the booster gearing from 1.5:1 to 1:1, with larger volume cylinders to supply the same tractive effort. Tractive effort concerns led to an increase in boiler pressure to 200psi, and the requirement for a larger boiler. Some concern was also expressed about engaging the boosters at higher speeds, although it was accepted that the unitary ratio of 1:1 would make this easier.

The boilers also differed from standard C7 boilers in that their internal design followed Doncaster practice (rather than Darlington), and they had Robinson superheaters (rather than Schmidt). The internal tube arrangement of the boilers matched that of the Diagram 100 boilers used on the B17s.

When operated by regular engine crews, the C9s were reasonably successful. However, with 'common user' rostering, it was common for the C9s to be operated with crews who were unfamiliar with the boosters. This tended to result in neglect or even misuse of the booster.

The rigid wheelbase of the C9s was limited to the distance between the two driving axles, ie. only 7ft 7in. Combined with the even balancing of the three cylinder design, they ran well on track with S-bends.

With increasing numbers of Gresley Pacifics and the advent of the first Pacific A4s during the early/mid 1930s, the C9s were no longer required to work the heaviest expresses. Indeed, the Pacific A4s were timetabled to climb Cockburnspath with 312 tons at an average speed of 55mph - making the C9 booster experiment rather redundant! Hence at the end of 1936, it was decided that the boosters could be removed. They were removed in December 1936 (No. 2171) and February 1937 (No. 727), although official authorisation for removal was dated 22nd April 1937.

Both locomotives were originally allocated to York as C7s, but moved to Gateshead after rebuilding. In 1939, both moved to Tweedmouth until November 1940 when they moved back south to Heaton. The bulk of their work consisted of secondary express services between Edinburgh, Newcastle, and York. They also hauled many of the express freight services such as meat and fish trains. Sometimes they were seen hauling the top express passenger services such as the 'Flying Scotsman', double headed with a C7. About the only sightings off the main line concern No. 2171, which was sometimes seen on the Newcastle to Carlisle line after its booster had been removed.

With non-standard boilers, withdrawals of the two C9s were relatively early. No. 2171 was withdrawn in April 1942, and No. 727 was withdrawn in January 1943.

Technical Details

| Cylinders (x3): | 16.5x26in. | |

| Motion: | Stephenson | |

| Piston Valves: | 7.5in. diameter | |

| Booster Cylinders (x2): | 10.5x14in. | |

| Boiler: | Max. Diameter: | 5ft 7.25in |

| Pressure: | 200psi | |

| Diagram No.: | 104 | |

| Heating Surface: | Total: | 2317.6 sq.ft. |

| Firebox: | 203 sq.ft. | |

| Superheater: | 417 sq.ft. (24x1.2in) | |

| Tubes: | 1178.4 sq.ft. (143x 2in) | |

| Flues: | 519.2 sq.ft. (24x 5.25in) | |

| Grate Area: | 30 sq.ft. | |

| Wheels: | Leading: | 3ft 7.25in |

| Coupled: | 6ft 10in | |

| Trailing: | 3ft 8in | |

| Tender: | 3ft 8in | |

| Tractive Effort: | (@ 85%) | 20,012lb |

| Booster Tractive Effort: | (@ 71.5%) | 5,000lb |

| Total Wheelbase: | 55ft 7in | |

| Engine Weight: | (incl. tender) | 135 tons 8cwt |

| Max. Axle Load: | 20 tons 1cwt |

Preservation

Neither of the C9 locomotives survived into preservation.

Models

I am not aware of any models of the C9s in any scale.